People involved in the neurodiversity movement have long used the concept of “aspie supremacy” (coined by Mel Baggs) to denote a certain ideology that may superficially look like neurodivergent liberation politics but is in fact anathema to our liberation.

As I understand it, the aspie supremacist is defined by the way in which they reclaim what they often call ‘Asperger’s syndrome’, ‘high-functioning autism’, or being an ‘aspie’. (It is important to note that these terms are now outdated, but we will use ‘aspie’ here because we are describing people who often self-identify as such.) At base, Fergus Murray sums aspie supremacy up well when they write that it is based on the idea that ‘aspies’ somehow “have extraordinary powers which not only make their existence worthwhile, but make them better than other people.” Most often, this project is based on them showing that their form of autistic cognition is superior to that of autistic people who also have cognitive or intellectual disabilities. Sometimes, they go so far as suggesting aspie cognition is superior to neurotypical cognition.

Aspie supremacists also often draw on evolutionary logics to justify their position and to naturalise their purported superiority, with certain autistic “strengths” framed as evolutionary adaptions. This mirrors eugenic theory and social Darwinism more generally, which precisely draws on the theory of evolution by natural selection to rank people, and as often as not, races, into hierarchies based on their purported natural traits and abilities. Hence we call it is aspie “supremacy” in the sense that it mirrors the eugenicist logics of white supremacy; and it is also “aspie” (rather than “autistic”) supremacy, since it actively excludes many other autistic people, including any perceived as having below average intelligence.

There are many problems with aspie supremacy. The most central is that rather than aiming at collective liberation by fighting the logics of racial capitalism – and thus ableism and fascism – it aims at showing that a small number of autistic people fit its norms better than has been recognised so far. Their autistic pride is thus of a hyper individualistic and competitive sort, based on comparing themselves to the purportedly lower abilities of others, to justify their superiority. This then reinforces the Social Darwinist logics of racial capitalism rather than challenging that system, helping a select few (almost always male, cishet, white, able-bodied middle class) autistics gain more respectability at the expense of other disabled people, especially those who are multiply marginalised.

A useful way to spot the difference between neurodivergent liberation politics and aspie supremacism is often to look at the formula for pride proponents of each have in mind. As a neurodivergent liberation proponent, when I talk of disability (or neurodivergent or autistic) pride I am talking about pride in a collective sense: pride in our shared disabled and autistic culture, in our forms of care, in our histories of resistance, and so on. This kind of collective pride is not the same as being proud of, say, my individual abilities or strengths, understood as superior to those of other people. In short, neurodivergent pride is a collective tool for fighting systemically imposed shame, not a reinforcement of the cultural logics of ableism then used to shift our shame onto others.

As a Mad person I likewise understand my sense of Mad pride as something collective and cultural. The Mad pride events I’ve attended have precisely been forms of collective action, celebrations of collective resistance, and so on, not declarations of our superiority. More broadly, the Mad Pride movement, as I understand it, fits more with this kind of understanding than the hyper individualistic logics of aspie supremacy. For the most part it has been like this since the beginning. There are of course complex debates about the exact meaning and implications of Mad pride (see, e.g. this excellent article) and these are important to have. But by and large the collective approach to Mad Pride is the kind I associate with the politics of Mad liberation.

My interest here is something hitherto unnamed, which I name as Mad supremacy. I call it this because it is roughly the same as aspie supremacy, except it is focused on Madness rather than autism. Mad supremacy thus tries to base Mad pride on showing that Madness is not really insanity, disability, or illness, but is instead a positive set of traits that are fundamentally adaptive, functional, or rational – and, vitally, fundamentally unlike, indeed superior to, other kinds of disability.

To avoid misunderstanding, I am not suggesting that all, or even most, positive reclamations of Madness are forms of Mad supremacy. They are certainly not. Neither are all or most challenges to purely deficit based or pathologising framings of Madness. To the contrary, with both Neurodivergence and Madness it is vital to challenge the ways we have been constructed as purely deficient or pathological, especially when these constructs are used to dehaumise, control and incarcerate us. I have thus often defended the reclamation of Madness and Neurodivergent diagnoses, even while I critique overly individualistic approaches. When it comes to Mad supremacy, it is the specific logic with which we work that is important, not the claim that pathologisation should be rejected or that Madness can be positive.

To understand logics of Mad supremacy, it is worth considering that to some extent, it finds a base in what I’ve called the ‘comparativist critique’ of mental illness found primarily in the libertarian Szaszian strand of anti-psychiatry and critical psychiatry. As I have detailed at length, this is ‘comparativist’ because it is based on comparing what are usually called mental disorders with bodily illnesses, in order to show that the former are not ‘real’ disorders and are in fact forms of comparatively normal functioning. While challenging pathologisation is itself not a problem, and while comparisons are of course sometimes useful, this argument is distinguished by invoking a naturalised conception of bodily illness or disability as inherently deficient, to claim that mental illness is actually comparatively normal, meaningful, or so on. It is a way of saying: we are not like them, we are normal while they are not. It is by trying to show that mental disorder is comparatively superior in its functioning, that the comparativist critique tends to reinforce ableist logics (not to mention it’s commitment to the kind of bodily essentialism associated with transphobia and so on).

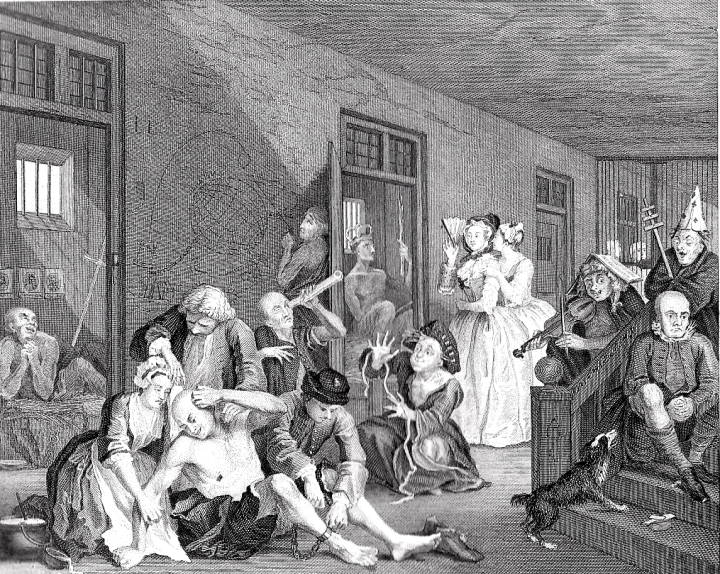

Mad supremacy likely dates back at least to efforts to associate (white) Madness with ‘genius’ in 18th century Europe. But today the Mad supremacist is most often encountered on social media or in chat rooms. While there is no perfect archetype, the Mad supremacist in the wild usually has several related tenancies. First, like the aspie supremacist they are typically (both socially and epistemically) male, middle class, white, cishet, and able-bodied, or as close to this as possible. They will typically adamantly deny that their favoured form of Madness is illness, disability, or insanity by comparing it to people whose bodies or minds they consider naturally and objectively dysfunctional, suggesting that their favoured form of Madness is comparatively superior in terms of being more meaningful, functional or rational. Like proponents of the comparativist critique, they also tend to share other similar political commitments (such as to a naturalised conception of the sex binary) that are based on closely related logics. And vitally, like the aspie supremacists, the pride of the Mad supremacist is not about collective history, culture, and resistance; it is, rather, about their cognitive superiority to one group or another.

While Mad supremacy has generally remained on the fringes of Mad activism, I now see it more often than even just a few years ago. Indeed, something approaching this kind of argument recently made its way into an academic journal. In his article Madness and Idiocy, philosophy professor Justin Garson – who, in line with the aspie supremacist approach, has previously spent much time arguing that Madness and certain forms of neurodivergence are really evolutionary adaptions – precisely proposes that Mad Pride could be based on a comparison between Madness and ‘idiocy’ (an old term roughly denoting people with developmental or cognitive disabilities) that he explores in late modern philosophy. To establish this, Garson quotes a variety of related late modern views, such as an 1818 text by Heinroth, that distinguished Madness as “disturbances of soul life” from idiocy, whereby “soul lives […] have never begun to exist” (1818). But what is most important for Garson is that in this period, idiocy increasingly became associated with below “average” intellect and the absence of reason, while Madness was increasingly associated with average or above intelligence and merely disrupted (but not absent) rationality.

With such views in mind, Garson’s own argument is that instead of being contrasted with sanity, as it commonly is today, Madness can instead be contrasted with idiocy, as it was in the late modern period. For Garson, looked at this way we can see that Madness, unlike idiocy, is really a specific form of reason (and thus sanity) rather than a lack of it. Based on this – and this is his key point – Garson suggests this may provide a philosophical foundation for Mad Pride. That is, he associates the basis of Mad Pride with showing that Madness can really be a form of rationality, rather than being, like idiocy, as his division frames it, an absence of reason or intellect. As a Mad person, according to this logic, I should (or can) ground my individual pride in my being rational (or, it seems, of above average intelligence), in contrast to how those called idiots were understood in the late modern period.

For anyone familiar with aspie supremacy, it will be hard to not see this as closely resembling the arguments aspie supremacists make in relation to autism and intelligence. Many of us, I hope, will be particularly wary of arguments that uncritically rely on dehumanising depictions of cognitively disabled people, such as the Heinroth text cited above. Many of us will also reject an equation for Mad pride that rules out including people with cognitive disability by definition. That said, while Garson refers to this as a “superior, refined definition of madness”, he stops short of fully endorsing the utility of this formula for Mad Pride (as justifying that would go beyond the scope of the article). Moreover, he also suggests that he doesn’t mean to imply anything about the value of people with cognitive disability today (although it is not at all clear why this wouldn’t follow, since that is precisely the logic he draws on and reproduces). To what extent Garson actually endorses the implications of the logics he proposes is thus left as something of a mystery.

In the same journal, Awais Aftab has already replied to Garson that Mad pride need not focus on proving one’s rationality and in practice is often more about politics and resistance. In response, Garson writes that he “cannot see how any form of mad activism can proceed without adopting a vantage point on madness which recognizes it as partly constituted by rationality”. And yet here lies the issue. It is not that I deny that Madness can be infused with reason (I don’t). It is also not just that this is simply not the issue that defines whether pride can be found. The deeper issue is that any logic that requires throwing others under the (eugenic) bus to establish pride in our purported superiority should be rejected, at least for those of us concerned with collective liberation.

In fact I do not think Mad pride needs justification. It is something we do, not something we ask permission for. Certainly for me – although perhaps not for everyone – the cultures of Madness I belong to and find pride in are defined not by superiority of intelligence or comparative rationality, but rather by our shared resistance to the very systems and apparatuses that ideologically produce rationality in the first place. And as rationality itself is part of what is oppressive, it is not an elite club I would like to join before kicking away the ladder.

It is unclear how widespread Mad supremacy is. From my experience, it seems largely restricted to the imperial core. But we live in an age of rising fascism and everything that comes with that. What I am certain about is that far from liberating us, supremacy-based logics, even if they did help a small number of Mad people gain more respectability, will only reproduce the ideology and systems of domination that keep sanism and ableism in place.

I think Eugenics is very misunderstood Darwinism. Darwin said that multiple different forms of life are the best form of evolution.

LikeLike